Explore excerpts from:

Family Secrets

My Mother Worked for Adolf Hitler

Her silence was the inheritance my mother left me. Maria Wałęsa had worked in Germany during the war. She never spoke about it. Twenty years have passed since her death, and I had learned to tuck the enigma of her silence into a deep corner of my mind that I rarely visit.

Then unexpectedly, I discovered my mother’s story in a history book. Her story wasn’t exactly in plain sight, but I had never bothered to look – and now here in black and white was the story my mother never wanted me to find: what it meant to be forced into service under Hitler’s regime, to be one of the innocent millions whose lives Naziism’s hateful grip had forever altered. And so began my search – not just for every detail I could find to imagine her journey, but for the woman who had chosen silence, leaving me to inherit both her secrets and her reasons for keeping them.

The Family Who Lived on the Other Side of the Wall

Finally, I learned the reason for the Switocz family’s eviction in May 1943 wasn’t what I had assumed – it wasn’t simply Germans coveting central Warsaw real estate. The eviction coincided with the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, when the Jews trapped behind those walls, facing the certainty of death in the camps, chose to fight back in a desperate four-week resistance that began on April 19.

As the Germans moved in to crush this uprising, the families along Mirowski Square – including my father’s – were suddenly ordered to flee. The Switocz family found themselves racing toward a courthouse basement on Miodowa Street, their entire world reduced to what they could carry in their arms. Within hours, they had abandoned everything that had made their apartment a home: Edward’s first stamp collection, his favourite track shoes, important papers that documented their existence.

16 Mirowski Square is indicated with a red arrow and dot.

The map of the boundaries of the Warsaw Jewish Ghetto is reprinted with the permission of the Polish Center for Holocaust Research. Click on map to zoom in.

Click on the image to zoom in.

Sixty-three Days

On the morning of October 5, 1944, Edward scraped a dull razor over the stubble on his face. He wiped away what grime he could without running water, and straightened his torn and dirty uniform. Then – and this is the detail that breaks my heart – with his head held high, he joined the surrendering Home Army insurgents – men and women – for their final march to Plac Bankowy.

As they walked through the rubble-strewn streets, the insurgents began to sing the Polish national anthem, “Jeszcze Polska Nie Zginęła,” meaning “Poland is Not Yet Lost.” Edward’s voice joined with those of his fellow soldiers and the civilians who had gathered to watch them pass. The small crowd was in tears. At Plac Bankowy, the insurgents arranged themselves in a straight formation to face the victorious Germans. After sixty-three days of fighting to liberate his city and restore Polish independence, Edward found himself surrendering a few streets from where he had played as a boy.

Edward stands on the far left. Marked with a red dot.

The Letter from lamsdorf

On the morning of the Nazi evacuation from the POW camp, Edward woke up earlier than usual. He rose from the upper bunk where he slept alongside six other Polish men, all fellow resistance fighters from the Warsaw Uprising. The bunk had no mattress, and a couple of wooden support planks were missing—burned for warmth in the small wood stove during the previous days. The Nazi guards had already moved others out of the camp, so Edward knew to be prepared.

He had packed a small satchel with his few belongings, including a family photograph and a letter he'd written on a camp form to his father, Piotr. The Germans had rounded up his parents at gunpoint during the Warsaw uprising—his mother sent to Ravensbrück, his father to Gross-Rosen concentration camp.

The letter was a tender, carefully worded communication to avoid censorship, filled with great respect and concern for his father's fate.

Dear Father

With great emotion, I received the package from Józio, and then, with a lump in my throat, I read his letter. The evidence of his friendship is touching, and I wrote to him about it. I was happy to hear that you are well and alive, but at the same time I am saddened that fate has brought you, at your age, instead of a well-deserved peace and rest, hard living conditions beyond human measure. Perhaps the good Lord will soon allow you to reunite with your family, for whose sake you have devoted your entire life. Write back quickly. What about Gorzkienicz? Wiesiek Polkowski is with me and asks about Durkowski, Kutkowski and Bazanski's in-laws who were at the court with you. Write me a lot about yourself. I am healthy and feel fine. I am leaving for a permanent camp.

Edek

The German post office returned it with a stamped message in German: Return! Impossible to deliver as the addressee is not in the camp. The returned letter was a sad confirmation that his father must have died in Gross-Rosen. Edward carried the returned letter in his satchel on the death march from the POW camp.

my father carried this photo on the death march

My father, Edward, also carried a photograph in his small sack on the death march from the POW camp. It was a photo taken just before the war of his family. My grandmother radiates happiness as she strides closely beside her younger daughter, Jadzia, who appears to be around thirteen. Jadzia sports a pair of charming Mary Janes, and my grandmother wears a striped summer dress and a hat tilted at a jaunty angle. Walking slightly behind them is my grandfather, who wears a dark suit and tie; a small, neat, dark moustache punctuates his more serious face. With his broad face full of youthful promise and a shock of blond hair pushed casually back from his forehead, Edward pops his head up behind his mother and sister. He has a slightly mischievous smile. I see the father I know on his face and imagine the family is hurrying to church on a Sunday morning.

I know the photo. My father hung onto it his entire life. It is the only photo of my grandparents that I have ever seen.

She Was Marked by the Letter P

The next step for Maria was to have her photo taken for her Arbeitskarten – the forced labour identification card. I hold the extra print from that day, a passport-size photo my mother kept for sixty years. A dark-haired girl stares out at me, her eyes wide with fear. She’s wearing that tie-front blouse that I imagine her mother might have fixed when the men came to take her away. Maria had just turned twenty, two weeks earlier. On the back, a faded stamp reads “Photohaus Jäger, Sulzbach-Rosenberg.” Perhaps a female clerk pasted the first print onto her ID card.

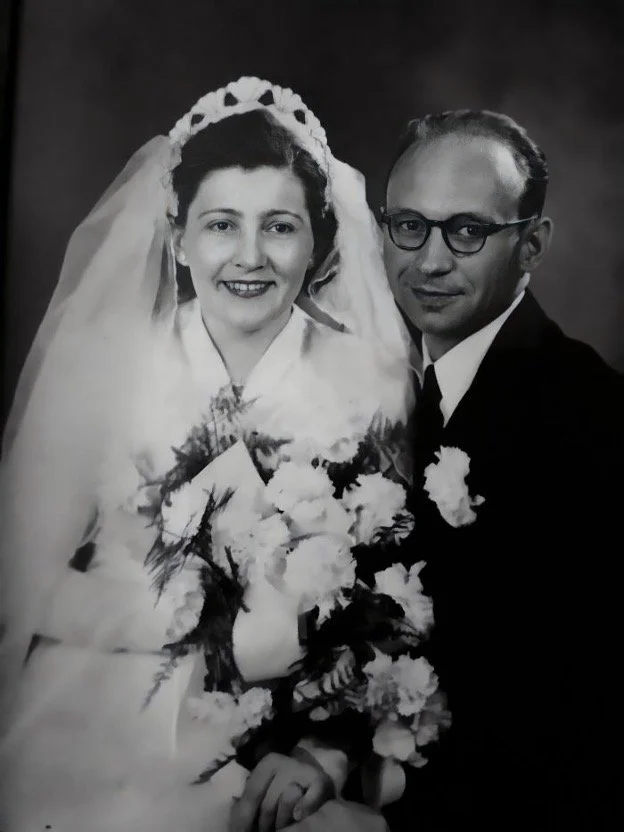

The Wedding dress

I searched for the owner’s obituary, tracked down his children, and sent an email to thank them all these years later for the wedding dress. My father’s regret that he and my mother hadn’t appropriately thanked her employers for the gift of a wedding dress could finally be laid to rest. Soon, a gracious acknowledgement arrived in my inbox from a woman who had not yet been born when my mother had worked for her parents….

My sister still has the dress; it’s yellowing with age. You can see that it’s beautifully finished with hand-stitching along the seams, clearly the work of a talented seamstress. Each covered button is handmade. I think about her going for fittings, probably the first time in her life she’d worn something so beautiful, and it just breaks my heart in the best way.